An invisible mask? Wearable air curtain, treated to kill viruses, blocks 99.8% of aerosols

Headworn tech from U-M startup could protect agricultural and industrial workers from airborne pathogens.

Headworn tech from U-M startup could protect agricultural and industrial workers from airborne pathogens.

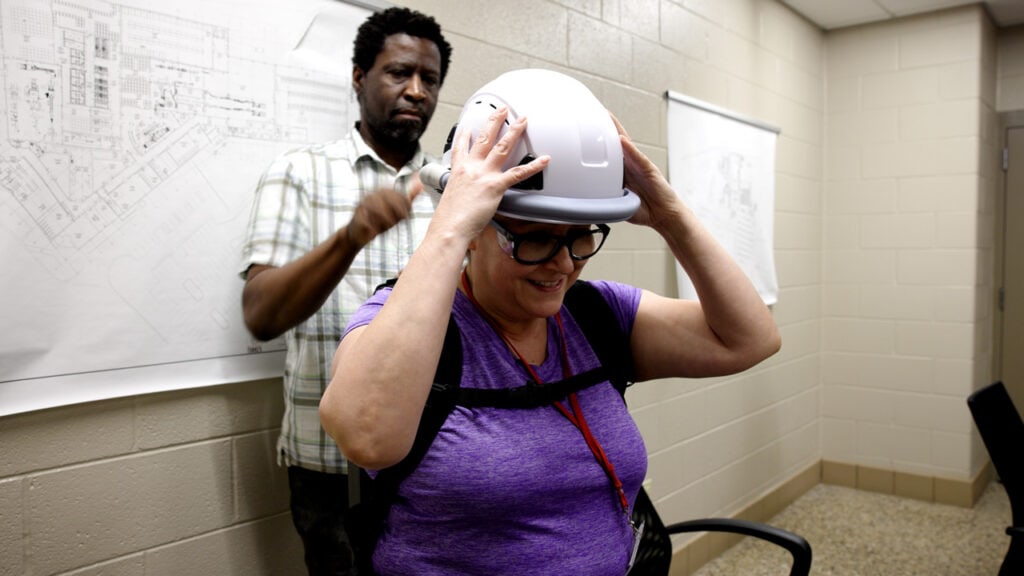

An air curtain shooting down from the brim of a hard hat can prevent 99.8% of aerosols from reaching a worker’s face. The technology, created by University of Michigan startup Taza Aya, potentially offers a new protection option for workers in industries where respiratory disease transmission is a concern.

Independent, third-party testing of Taza Aya‘s device showed the effectiveness of the air curtain, curved to encircle the face, coming from nozzles at the hat’s brim. But for the air curtain to effectively protect against pathogens in the room, it must first be cleansed of pathogens itself. Previous research by CEE’s Herek Clack, Taza Aya co-founder, showed that their method can remove and kill 99% of airborne viruses in farm and laboratory settings..

“Our air curtain technology is precisely designed to protect wearers from airborne infectious pathogens, using treated air as a barrier in which any pathogens present have been inactivated so that they are no longer able to infect you if you breathe them in,” Clack said. “It’s virtually unheard of—our level of protection against airborne germs, especially when combined with the improved ergonomics it also provides.”

Fire has been used throughout history for sterilization, and while we might not usually think of it this way, it’s what’s known as a thermal plasma. Nonthermal, or cold, plasmas are made of highly energetic, electrically charged molecules and molecular fragments that achieve a similar effect without the heat. Those ions and molecules stabilize quickly, becoming ordinary air before reaching the curtain nozzles.

Taza Aya’s prototype features a backpack, weighing roughly 10 pounds, that houses the nonthermal plasma module, air handler, electronics and the unit’s battery pack. The handler draws air into the module, where it’s treated before flowing to the air curtain’s nozzle array.

Taza Aya’s progress comes in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and in the midst of a summer when the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have reported four cases of humans testing positive for bird flu. During the pandemic, agriculture suffered disruptions in meat production due to shortages in labor, which had a direct impact on prices, the availability of some products and the extended supply chain.

In recent months, Taza Aya has conducted user experience testing with workers at Michigan Turkey Producers in Wyoming, Michigan, a processing plant that practices the humane handling of birds. The plant is home to hundreds of workers, many of them coming into direct contact with turkeys during their work day.

To date, paper masks have been the main strategy for protecting employees in such large-scale agriculture productions. But on a noisy production line, where many workers speak English as a second language, masks further reduce the ability of workers to communicate by muffling voices and hiding facial clues.

“During COVID, it was a problem for many plants—the masks were needed, but they prevented good communication with our associates,” said Tina Conklin, Michigan Turkey’s vice president of technical services.

In addition, the effectiveness of masks is reliant on a tight seal over the mouth and noise to ensure proper filtration, which can change minute to minute during a workday. Masks can also fog up safety goggles, and they have to be removed for workers to eat. Taza Aya’s technology avoids all of those problems.

In his research with CEE, Clack has spent years exploring the use of nonthermal plasma to protect livestock. With the arrival of COVID-19 in early 2020, he quickly pivoted to how the technology might be used for personal protection from airborne pathogens.

In October of that year, Taza Aya was named an awardee in the Invisible Shield QuickFire Challenge—a competition created by Johnson & Johnson Innovation in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The program sought to encourage the development of technologies that could protect people from airborne viruses while having a minimal impact on daily life.

“We are pleased with the study results as we embark on this journey,” said Alberto Elli, Taza Aya’s CEO. “This real-world product and user testing experience will help us successfully launch the Worker Wearable in 2025.”

Clack and the University of Michigan have a financial interest in Taza Aya.

Marketing Communications Specialist

Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering