Fred B. Pelham: building bridges

The first African-American Michigan engineering graduate established a sturdy reputation for designs that last.

The first African-American Michigan engineering graduate established a sturdy reputation for designs that last.

By Randy Milgrom

Frederick Blackburn Pelham was the first African-American to receive an engineering degree from the University of Michigan. An excellent student who would become president of his graduating class, Pelham earned a bachelors of science degree in civil engineering in 1887 and immediately began a career in bridge design and construction with the Michigan Central Railroad.

In his brief but highly productive career as a civil engineer, Pelham became known for designing bridges that were built to last – though this was less true, unfortunately, of Pelham, who died at home in 1895, reportedly of acute pneumonia, at the tender age of 30 years old.

Early Life

Fred Pelham was born in Detroit, Michigan, on November 7, 1864 – the year the Civil War ended. His parents, Robert and Frances Butcher Pelham, were free persons and landowners in Virginia, but in the 1850s they fled the state – where they still were subject to widespread discrimination and onerous legal restrictions, including a prohibition against obtaining an education. The family made several stops before settling in Detroit.

Fred was the youngest of the seven Pelham children (three girls and four boys). His father was a mechanic as well as an accomplished building contractor and mason, and he passed those skills on to Fred.

But the Pelham family stressed strongly the value of a good education, and Fred would become the fifth member of his family to graduate high school at a time when few Americans of any race did so. Fred followed the high standards set by his older siblings, several of whom became professionals playing significant roles in public life as newspapermen and government officials.

Pelham, the Michigan Engineer

Fred was said to be a “quick learner and a diligent student,” and he graduated from Detroit High School with highest honors. At Michigan, Pelham “mastered the difficult mathematics needed to excel in civil engineering,” received “superior” grades, and graduated “at the head of his class.” He was said to be “quiet and gentlemanly,” and earned the admiration and respect of his classmates.

As graduation approached, the Michigan Central Railroad was in the market for civil engineers. Railroad officials approached the Michigan engineering faculty for recommendations, and Pelham was one of two students Professor Ezra Greene offered up as prime candidates for employment. Pelham was hired in 1887 and he remained at the railroad until his untimely death in 1895.

Pelham’s employment with the Michigan Central Railroad – though brief – was prolific. His craftsmanship did not go unnoticed, and he was promoted more than once, rising to become “acting 1st Assistant Engineer” before the age of 30. He is credited with designing and building approximately 18 to 20 bridges throughout Michigan that are known for their architectural form and strength. Pelham’s structures have held up well for more than a century, spanning roads and rivers along the Michigan Central Line between Detroit and Chicago and providing safe passage for hundreds of thousands of trains – including the Amtrak passenger cars that continue to pass through Ann Arbor at least twice every day.

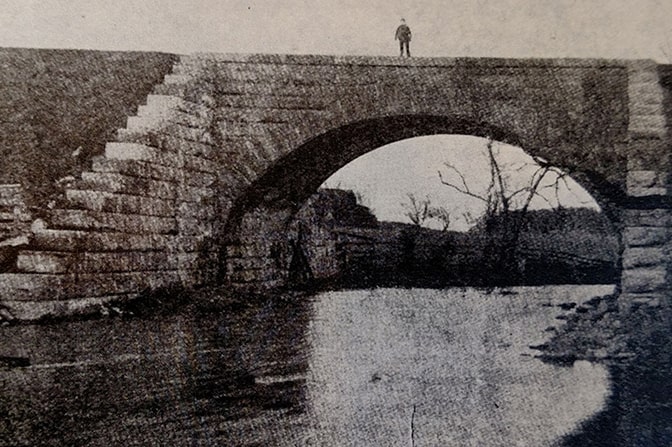

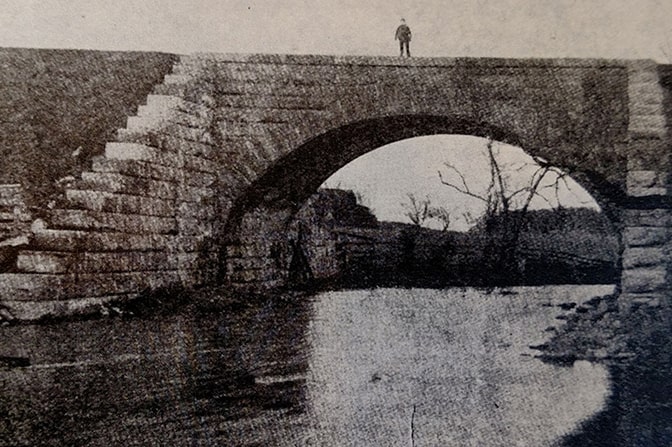

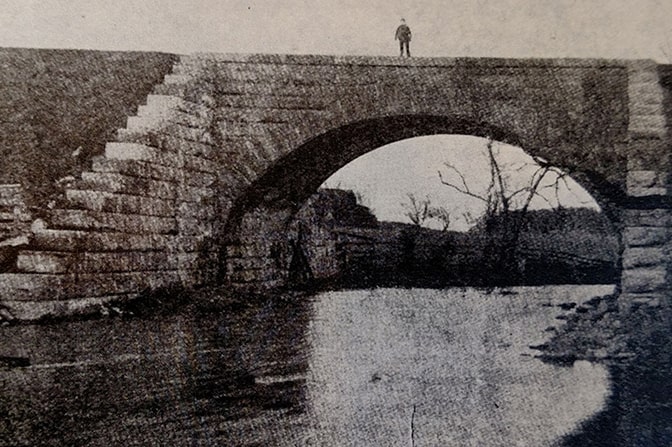

The Skew Arch Bridge

Among the more famous and unusual of Pelham’s creations is the so-called “skew arch” bridge located in Dexter, Michigan, just northwest of Ann Arbor – though there’s a more impressive Pelham-designed bridge, also within the Dexter city limits, whose much higher arch spans Mill Creek.

The skew arch (a design used when bridges are not perpendicular to crossings) passes over Dexter-Pinckney Road at the northwest edge of town, where it has received a great deal more attention because drivers tend to have to slow down to navigate its narrow, one-lane opening. The bridge originally accommodated pedestrians and horse-drawn buggies – and then a few automobiles. But once traffic increased, officials posted extensive signage to warn motorists of its mere 11 feet, 10 inch clearance.

Before constructing its elegant stone arch, a temporary wooded frame was installed under the rail bed. The soil the laborers had dug out was then used to raise the banks and straighten out Mill Creek as protection for the new bridge. Masons collected stones for both bridges and sized them by hand, and onlookers were said to be impressed by the strength of the bridge and the perfect fit of the stones that Pelham and the other workers had carved and used. For many years Michigan Engineering students would make field trips to visit the bridge and study its skew arch.

The plaque that long ago was placed near the skew arch bridge by the Michigan Central Railroad contains several names, but Pelham’s is omitted. It has been speculated that this is because only higher officials were generally so honored – or because of Pelham’s race.

Quiet Trailblazer

In his too-short life Pelham managed to perform other good works outside of his employment. Following his graduation from Michigan he had returned to live with his parents in Detroit, where he was involved with the development of the interurban electric railway system there. Pelham also was a member of the Michigan Engineering Society and the YMCA, and he taught Sunday school at Detroit’s Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church.

Sources include: The Michigan Manual of Freedmen’s Progress (John M. Green, 1915); Historic Highway Bridges of Michigan (Charles K. Hyde, 1993); Michigan railroad bridges bear U-M graduate’s stamp (Ann Arbor News 2000); African American Architects: A Biographical Dictionary, 1865-1945 (edited by Dreck Spurlock Wilson, 2004); and The Dexter Underpass (Ann Arbor Observer, Community Observer, Spring 2007).